Scrolling is the new smoking

Tech giants have copied Big Tobacco’s playbook - and it works.

Smartphones are the new cigarettes.

Technology companies are using the same playbook tobacco companies once did: design for addiction and normalise behaviour.

Compulsive, embedded phone use didn’t happen by accident, and it isn’t inevitable.

If you like this essay, share it with others. If you’re a regular reader, and you can afford it, please become a paid subscriber.

I took the train home on Wednesday. Almost every person boarded with their phone in their hand, some already lit up and ready to go. In my carriage, there were two people whose faces weren’t lit up with the glow of their phones. The vibe is eerie. Rows of silent people – heads bent, brows furrowed, mouths set in a grim line.

It's a normal 2025 scene, a vignette of our time, the period drama of the future.

I’ve been rewatching Mad Men, which oozes 60’s excess. Smoking is everywhere – bedrooms, restaurants, planes, workplaces, and more. It looks naughty and glamorous and as a former smoker, I almost feel myself exhale.

Betty Draper smokes through every domestic chore; a tendril of cigarette smoke wisps alongside as she tends children, or prepares dinner (or, in one unforgettable scene, shoots the neighbours’ pigeons with a shotgun.)

It seems wild, now, that smoking was so ubiquitous. Imagine the smell of Betty‘s hair! Was everyone coughing all the time? How did non-smokers cope?

We can shrug: it was the time. Absurd in hindsight, but this is how things work: we know better, then we do better. Except social norms are rarely that simple - especially when there’s money to be made from them. Which there usually is.

What feels normal was once radical, and what we mock was once invisible. Sterling Cooper (Mad Men’s ad agency) represent tobacco company Lucky Strike, a gig which becomes increasingly difficult as attitudes toward smoking evolve and start to turn. We see the manipulative marketing tactics and watch as new restrictions make this hard.

But there is plenty we don‘t see.

Addiction is by design

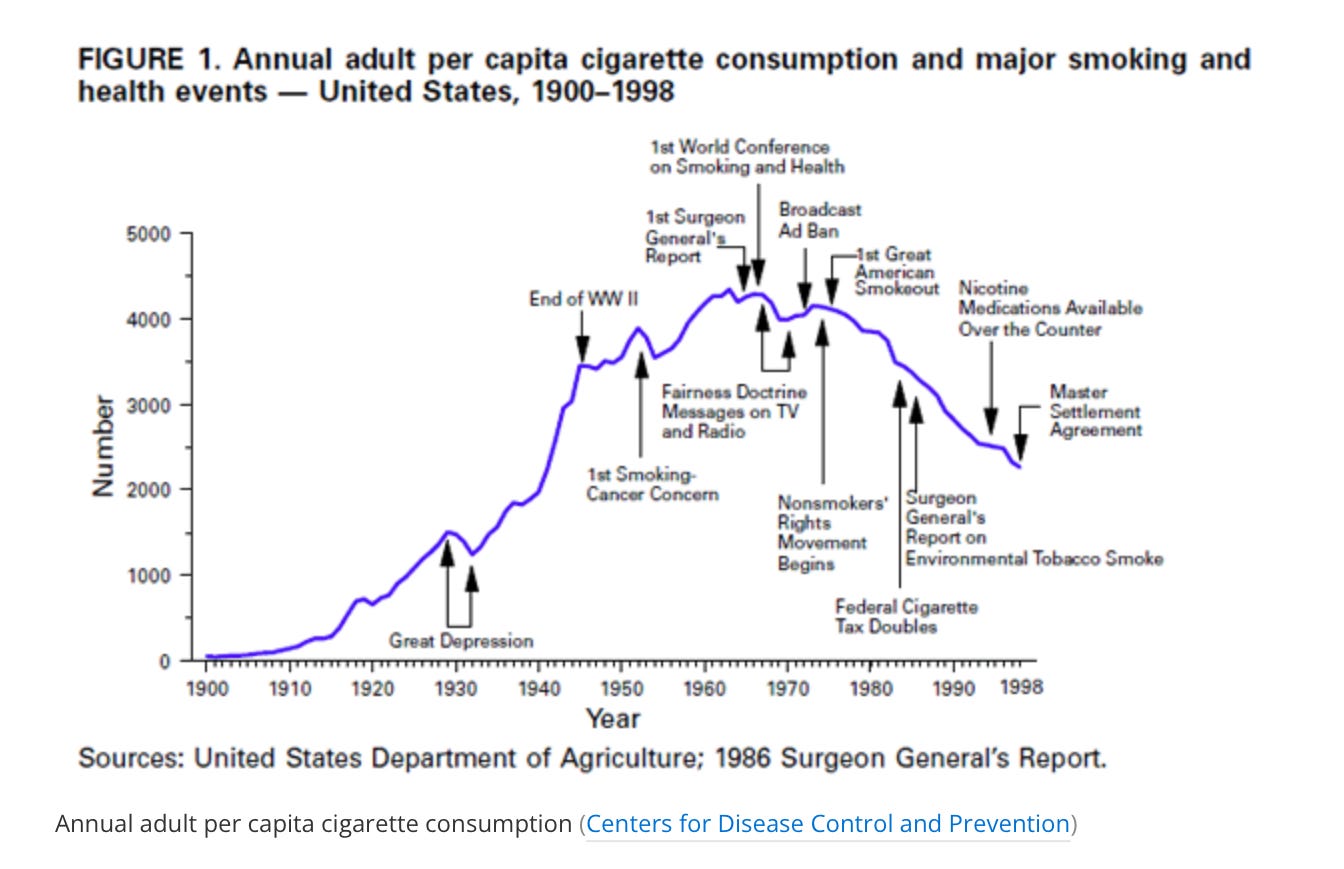

Mad Men-level smoking was a new phenomenon.

Before WWI, most smoking was done by labourers: loose tobacco packed in a pipe. The rise of cigarettes in the 20th century required strategic marketing and government collusion. Tobacco companies targeted troops and lobbied governments, sneaking cigarettes into ration packs and commissaries.

Soldiers were a great market – bored, stressed, and with little concern for long-term health. During WWII, authorities issued 50 weekly cigarettes to every Kiwi solider. The habit then went home and infiltrated civilian life.

In the late 50s, smoking peaked. Public health caught up and tobacco companies got more creative. They engineered more addictive products, lobbied hard and launched covert operations.

It worked. Tobacco use is still the leading cause of preventable death in the world, killing over seven million people every year. Tobacco companies still sell billions of products every year and have shifted into the lucrative and growing vape market.

Despite large settlements and worldwide regulation, no country has eradicated or outlawed smoking. New Zealand got close, with our world-leading and universally supported tobacco endgame policy. But when the government changed, tobacco companies intervened to have it overturned. They mobilised shopkeepers in a ‘Save Our Stores’ astroturf campaign and fed politicians talking points to shape a new policy that would favour the tobacco industry.

This pattern: hook, normalise, escape accountability – is familiar and reliable. It has been effective for tobacco, pharmaceutical and oil companies - and now, technology.

Tobacco products are optimised for addiction

Tobacco companies make design choices that make cigarettes as addictive as possible.

They genetically engineer crops to double nicotine. Add sugar, licorice, and ammonia to increase the speed and volume of nicotine absorption and bind nicotine to brain receptors. Poke ventilation holes in filters that require you to suck harder, boosting nicotine delivery. These changes kill millions – today’s smokers are more likely to develop lung cancer than smokers of 50 years ago.

Vapes were originally a quit-aid, but that changed when Big Tobacco moved in. Now, vapes are bigger, cheaper, and more addictive – tobacco companies cranked up the nicotine in vapes by almost 300% between 2017 and 2022. According to Andrew Huberman, vaping is to smoking what crack is to cocaine.

These fruity smoke machines look increasingly pre-cancerous and leach high levels of toxic heavy metals like lead, nickel, and chromium. The next public health crisis is unfolding, driven by the same companies who’ve never stopped selling addictive, deadly products to vulnerable people. Even the original troop-targeting strategy still works, with the UK government adding free cigarettes to 2024 ration packs for Ukrainian soldiers.

Nicotine ain’t got nothin’ on news feeds

In 1976, under 50% of the population smoked.

In 2025, over 90% of people have a smartphone in their pocket.

Like cigarettes, smartphones are engineered for addiction. Persuasive design elements like pull-to-refresh, notifications, and algorithmic feeds reinforce phone checking habits, extend screen time beyond intended boundaries, and keep us distracted.

Aza Raskin, creator of the infinite scroll (remember when news used to… finish?) and star of The Social Dilemma, regrets it’s invention and has since gone on to found the Center for Humane Technology. According to Raskin, infinite scrolling alone costs the world the equivalent of 200,000 hours per day in wasted time and productivity.

This was before the explosion of short-form vertical videos like TikTok and reels – the latest crack-to-cocaine development to cook our brains. The AI behind these feeds monitor your every swipe, pause - even battery level! - to serve ever-selective content precisely designed to keep you there. Crack, indeed.

And you’re never really off the phone. Push notifications and the prospect of streaks, likes, or a new Wordle keep your popcorn brain scattered and jumpy. The average person picks up their phone between 60 to 200 times a day. Boredom? Who needs it. We’ve got a shiny, smooth, perfectly weighted device in our pockets with the entire universe inside.

Your biology has been hijacked

Red notification badges and incoming likes trigger dopamine hits, exploiting the brain’s reward pathways.

And turning them off may not help - once we’ve been wired to expect notifications, hitting do-not-disturb might improve productivity, but leave us feeling anxious and out-of-the-loop instead. As for productivity, we could do with some, with all that smartphone use shrinking our attention spans, spiking our anxiety, and reducing our capacity for cognitive processing.

None of this is your fault. Tech companies hire armies of attention engineers, cognitive psychologists, and behavioural economists to deploy against you. You are no match for thousands of experts whose job is to keep your eyeballs stuck to the screen.

According to Stanford psychiatrist Anna Lembke, author of Dopamine Nation, these features corrupt and ‘druggify’ a hard-wired desire for connection, “making us vulnerable to compulsive overconsumption”.

These apps can cause the release of large amounts of dopamine into our brains' reward pathway all at once, just like heroin, or meth, or alcohol. They do that by amplifying the feel-good properties that attract humans to each other in the first place.

- Anna Lembke

Habits cost more than we realise

Scrolling is like eating KFC – alluring from a distance, feels good when you’re doing it, and invokes instant regret.

According to Lembke, that happens because when you sign off from a dopamine hit, the brain is “plunged into a dopamine-deficit state.” We then feel guilty when we emerge from a mindless scroll, which makes it difficult to achieve the things we wanted from the afternoon.

Any smoker who’s tried to quit knows this spiral. Addiction feeds on shame, which fuels the behaviour we’re trying to avoid. We feel bad about what we’re doing, then we crave a hit to relieve our discomfort. This cycle has you furtively scrolling on the toilet or checking a notification under the dinner table, even when you’re trying to quit.

And many people are trying to quit, at least a little. Just as almost all smokers want to quit smoking, most people wish they spent less time on their phone. And just as tobacco companies pedalled ‘personal responsibility’, tech companies would prefer you think you’re lazy and weak than admit they are manipulating your most basic human instincts.

Smoking and smartphones offer false relief

For smokers, cigarettes are gateways to relaxation.

Smoke breaks are like little holidays; a chanceto step outside and breathe. But it’s false relief. Nicotine is a stimulant. Cigarettes don’t calm your nervous system, they activate it – plus they constrict your blood vessels, make your heart pump harder and raise your blood pressure. The calm is just withdrawal wearing off.

After the honeymoon period wears off, smoking cigarettes is not about a desire for them – it’s about withdrawal from them.

Who hasn’t flopped down exhausted, and pulled out their phone, for a ‘break’? But it doesn’t calm us anymore than smoking does. The screen fires up our dopamine receptors and keeps us wired. The rest ain’t restful – and it carries opportunity cost. When brains don’t get a break between activities, our mood, energy and mental health suffers. “It’s very different from how life used to be, when we had to tolerate a lot more distress,” says Lembke. “We’re losing our capacity to delay gratification, solve problems and deal with frustration and pain in its many different forms.”

"The whole business of smoking,” Alan Carr once said, “is like forcing yourself to wear tight shoes just to get the pleasure of taking them off." There’s a similar paradox at work with phone-based productivity. Using your phone to order the groceries, communicate with friends, or do the banking might save you five minutes – but what about the five hours of unintended screen time it costs you in return?

Smartphone use has hidden costs

Your scrolling habit loses more than time.

Georgetown psychologist Dr. Kostadin Kushlev offers a way to explore hidden social costs: displacement, (what phones replace, like sleep or socialising) interference, (what they interrupt, like work or dinner conversation) and complementarity (the hidden cost of convenience.)

“Complementarity is not always positive because even that has opportunity costs.” explains Dr Kushlev. “Yes, I can use my phone to more efficiently order coffee, shop online, or do online banking, but I might miss out on opportunities to go outside or have a few friendly social interactions.”

This names something I’ve felt for a while – that even the benefits of my phone quietly erode something else. It forces bigger questions, not just about our phones, but about how we want to live, and what a good life looks like.

Unlike smoking, not all smartphone use is inherently bad. But even the useful or purposeful stuff comes at the risk of capture into the addiction vortex, and a suite of hidden social costs.

Commerce uses culture to survive

In Mad Men, smoking wasn’t just addictive, it was glamorous.

Smoking was written into scripts, woven into social rituals, and used to sell everything from cars to confidence. Tobacco companies used agencies like Sterling Cooper to invest in culture, because once something becomes part of everyday life, it stops feeling like a choice.

Today, smartphones aren’t just addictive, they’re necessary. They’re embedded in our schools, workplaces, daily habits and friendships. Kids aren’t just online for fun - they’re doing homework, communicating with their friends, keeping up with school notices. We’re not just scrolling, we’re paying bills, doing our jobs and finding directions.

In under two decades, smartphones have become our wallet, diary, TV, map, doctor, and best friend. The commodity strategy has been wildly successful.

Our kids will pay the price

The result looks a bit like the set of Mad Men, but instead of a cigarette dangling from everyone’s fingers, it’s a glowing little box. Look about in restaurants, as people sit across from one another glued to their screens, ‘phubbing’ their loved ones for a hit of screen-induced dopamine.

With adults behaving this badly, there’s little hope for kids who are uniquely vulnerable to the lure of the screen. Some commentators believe kids are more emotionally dysregulated and anxious due to smart phones and social media. Jonathan Haidt’s 2024 book The Anxious Generation argues that smartphone and social media use has driven sharp rises in anxiety, depression, and self-harm rates in teenage girls.

There was over 40 years between the troops in World War I receiving free cigarette rations, and smoking hitting its peak. In contrast, smartphone ownership has gone from 0 to 90%+ in less than 20 years. This is a recent and rapid development.

Opting out of ubiquity is never easy

The social and structural cost of not participating in smartphone culture is high. Parents fear social isolation or educational drawbacks for their children, if they force a ban, and cannot see how to function in society for themselves.

Ubiquity has its own momentum. It’s like kids playing in the street – once it stops being normal, it stops being safe. Once everyone’s on their phone, everyone’s on their phone. The more normal, inevitable and inescapable something feels, the harder it is to challenge. Luckily, we have a long-established track record of doing exactly that.

Normal is negotiable

Inevitability is a marketing strategy, we can push back.

Some of the tobacco industry’s most insidious tactics were instigated because of fear of the declining social acceptability of smoking.The most covert operations didn’t start until people started demanding safety and change.

With recent outcries against technology pervasiveness, and the push to free children from the shackles of phone addiction (Smartphone Free Childhood, B416), the groundswell is coming for scrolling, too.

Negative social norms do shift, even when we’re up against deep pockets, lobbying and manipulative design. Some shift quickly in response to legislation (smacking, plastic bags), while others take longer (racism, domestic violence). Australia’s ban on social media for under 16s is a global case study in the making, as we work out which category smartphones might belong to.

Changing social norms is no more of an accident that instigating them. Regulating harm, changing behaviour and protecting civilians from corporations takes months or years of committed activism from people willing to be annoying at best, pariahs at worst.

Smartphone saturation happened fast - could we undo it just as fast? We’ve surrendered our privacy, information, communication, media, education, entertainment, navigation and payment infrastructure to technology companies in just a few short years. Perhaps in a few more, that could look absurd.

We got smoking out of bars, flights, and workplaces; we can surely create new norms for technology. If we want to. Tech giants almost definitely won’t collapse. They’ll get creative, adapt, and invent whatever the vape version of a smartphone is. They’ll be fine – but will we?

The boys light up

As my train pulled out of the station, wobbling gently on its tracks, I watched people put their phones down, only to pick them up again moments later.

A blonde woman with bright lipstick and bold earrings had boarded the train in Wellington, with an older colleague. I saw her glance at her companion a few times, as if to make eye contact, or start a conversation. I watched her eyes move from her workmate’s face, flicker down to her screen, then move back down to her own phone, defeated. Simply having a smartphone nearby reduces attention and smiling between people.

In the Mad Men era, people worried about the social impact of newspapers. People didn’t talk anymore, because they had their face in newsprint. But there were only so many pages to turn. The newspaper was a finite resource. Once the entire internet entered our pockets, we became lost to a void.

As for me, I was feeling smug, staring out the window with my little notepad, phone safely tucked away in my bag. But I’d sent a text before I got on, and the itch to check whether I’d received a response made my hands and fingers restless.

For the purpose of the exercise (and to extend my smuggery), I resisted checking it for the duration of my journey home, scribbling notes about phones, culture, commerce and social norms.

On my walk home from the station, safely out of view of the people I’d been judging on the train, I pulled it out, lit up, and exhaled in a flood of cheap relief.

Til next week,

AM.

If you like this essay, share it with others. If you’re a regular reader, and you can afford it, please become a paid subscriber.

Such a good essay Alicia. You might find this article interesting. I’m not saying Scotland is leading the way but they recognise the problems mobile phones bring to kids lives at schools and are trying to address it. By all accounts it’s made a difference in a number of ways and the kids and teachers are benefiting from this change. https://www.thenational.scot/news/25142615.edinburgh-high-schools-ban-mobile-phones-scottish-first/

100% Alicia…and AI is about to wind that dial up another level, and then a week later, another level..as a grandparent that shits me.